Shama is from Bangladesh. She loves choral singing, but wonders if all choral music is religious.

Shama writes:

“I love singing and have been singing since I was 9. Although I started out with learning Bengali classical music, I have also been really interested in English music. I love listening to choral music.

But such opportunities are not available in our country, as far as I know. I really do not have much knowledge about choirs. I was hoping you can tell me about the significance of religion in choral music.

Church choir groups exist all over the world, including our country. But I think they would be reluctant to let me join them, as I am from a different religion. My parents will be negative about it too.

Do choirs always have to be religious? Are there choir groups who do not focus on the religious side of the music, but only on the beauty of it? If not in our country, hopefully in other countries?”

choir? choral music?

Not trying to be difficult here, but it depends on what we mean by ‘choir’ and ‘choral music’!

By ‘choir’ I mean a group of singers who come together on a regular basis to learn and perform songs in a formal or semi-formal way. Most choirs sing in four-part harmony with or without musical accompaniment.

“a body of singers who perform together. The […] term is very often applied to groups affiliated with a church (whether or not they actually occupy the quire) …”

The connection with churches is reinforced by the other meaning of the word ‘choir’:

“Architecturally, the choir (alt. spelling quire) is the area of a church or cathedral, usually in the western part of the chancel between the nave and the sanctuary (which houses the altar).”

However, the notion of the ‘chorus’ is pre-Christian and goes back to ancient Greek drama. The oldest unambiguously choral repertory that survives dates from 200 years BCE.

harmony singing and polyphony

There are many groups of singers throughout the world who sing regularly, but without the formality of a choir. In such cultures there is no separation between singer/ performer and audience. Everyone sings and everyone joins in. Children learn the songs from a very early age so there tends not to be any kind of formal training.

If you accept that a choir sings in harmony, then that immediately rules out the traditional music of many cultures. Asian cultures, for example, tend not to have a harmony singing tradition, whereas Eastern European cultures have a strong harmony tradition going back thousands of years.

I’ve written on the subject of harmony singing traditions in Why don’t you sing songs from India?

In the West, the term ‘choral music’ has come to mean music that is written down, has been composed by a known composer, is often ‘classical’, and is very often Christian church music.

But there are many ‘choirs’ who sing ‘choral music’ that doesn’t fit this tradition.

the role of the Christian church

I’m not an expert in this area by any means, so please take this as a very rough guide!

Harmony singing in the Christian church goes back to the 14th century in Western Europe. During the Renaissance, sacred choral music was the principal type of formally-notated music in Western Europe. It is still a very strong influence in the Catholic church and the Russian Orthodox church, as well as the hymn singing tradition of the Anglican church.

When the West began to colonise other countries, they took their religion and their music with them. This meant that harmony singing was introduced to cultures that had no such tradition.

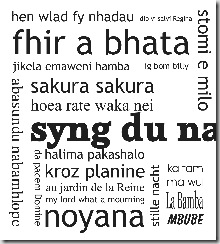

Countries such as New Zealand and South Africa embraced this new musical style with gusto and incorporated it into their own singing traditions. The legacy of this is the rich harmony traditions of Maori songs and South African church singing.

Although originally the Christian missionaries would have taught religious songs to these cultures, the harmony techniques have also been applied to folk songs and other non-religious music.

do choirs have to be religious?

The short answer is “No”.

If you like Western classical music, there is a lot of religious repertoire, but also a great deal of non-religious material.

If you like traditional and folk music, there are many cultures throughout the world which have strong, non-religious harmony singing traditions.

There are choirs throughout the world with are based in churches, but also many, many choirs which have no religious affiliation at all (in fact, I know of several choirs which completely ban any kind of religious music!), but which are based in the community that they serve.

I don’t know about Bangladesh I’m afraid, but I’m sure if you look hard enough you will find a non-religious choir.

can I sing religious songs if I’m not religious?

Some people have very strong objections to singing songs from religions other than their own. Some people who are atheists or agnostics refuse to sing any songs that have any religious overtones at all.

I don’t have a religious bone in my body, but I absolutely LOVE gospel music, Russian church music, shape note songs, South African church songs, Jewish Niggunim, etc. etc. Does that mean I can’t sing them?

I’ve written about secular vs. religious songs in The devil doesn’t always have the best songs!

As long as I respect the tradition that a song comes from, and as long as I’m not singing anything overtly religious (personally I draw the line at singing about Jesus, but I’m happy to sing about the Lord or the Spirit), I continue to sing and share beautiful music. After all, the music was created by human beings and is a celebration of our inner spirit whether you are religious or not.

There is a very interesting discussion on ChoralNet about a pagan woman who asks if she can be a choral conductor. She believes that:

“no matter how PC or multicultural people try to make it – there are no SATB choirs anywhere in the world outside of the Christian tradition that created it.”

I’m not sure that I totally agree with that, but it has sparked off an interesting discussion about whether you need to believe in what you’re singing or conducting.

Chris Rowbury's website: chrisrowbury.com